“When People Criticize Zionists They Mean Jews, You Are Talking Antisemitism” Martin Luther King Jr, A proud unapologetic Zionist

More exact words were never said. They were told by the great civil rights leader, The Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., the American hero whose life and dream of please and equality America celebrates on Monday, January 16trh.

Dr. King was a strong supporter of Jewish Issues. He fought for the freedom to observe all faiths, was a proud unapologetic Zionist and fought to release the Jews trapped in the Soviet Union. One of his closest allies and friends was Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, a Polish-born American rabbi considered one of the leading Jewish theologians and philosophers of the 20th century. He was a leader of the civil rights movement. In many pictures of 1960s civil rights protests, including the famous one in Selma, the Reverend and Rabbi marched close together in the front line. The two great men of faith forged a close alliance between African American and Jewish National Leadership.

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel (pictured above with the beard) marched with Martin Luther King Jr. on the road to civil rights. Rev.King marched with the Jews on the way to a secure Israel.

“At the first conference on religion and race, the main participants were Pharaoh and Moses. The outcome of that summit meeting has not come to an end. Pharaoh is not ready to capitulate. The Exodus began, but is far from having been completed.”

Those were the words with which Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel opened his address at the 1963 National Conference on Race and Religion in Chicago. At that conference, Rabbi Heschel first met the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the keynote speaker at this national gathering.

Interestingly in their speeches, each of the holy men chose to quote the same passage from the book of Amos, not knowing what the other would say. His vision of a world where “Let righteousness roll down like waters and justice like a mighty stream.”

After the two met at that conference, they became close friends and allies, working together to achieve equality for their communities.

Theologically as well as politically, King and Heschel recognized their own strong kinship. For each, there was an emphatic stress on the dependence of the political on the spiritual, God on human society, the moral life on economic well-being. Indeed, there are numerous passages in their writings that might have been composed by either one. Consider, for example, Heschel’s words: “The opposite of good is not evil, the opposite of good is indifference,” a conviction that he translated into a political commitment: “In a free society, some are guilty, but all are responsible.” King writes, “To accept passively an unjust system is to cooperate with that system.” In so doing, he went on, “the oppressed becomes as evil as the oppressor.” Not to act communicates “to the oppressor that his actions are morally right.”

Reverend King knew that the only way his dream would be realized was to invite people of all colors and beliefs to join him. Rabbi Heschel knew the struggle for civil rights was a holy one, and participation was required by Jewish law. The two prophets of different faiths soon became fast friends and allies. When Dr. King was assassinated on April 4, 1968, he and his family were scheduled to be guests at Rabbi Heschel’s family’s Passover Seder eight days later.

Sadly after Reverand King was assassinated, some new African American leaders felt the Jews were not their allies but their competition. That competitiveness quickly morphed into Antisemitism.

The Civil Rights movement’s leadership was inherited by people like Jesse Jackson, who saw the Jews as their competition for achieving middle-class status. Unlike Reverend King, who was a believer in the Zionist mission—a Jewish State in their eternal homeland, black leaders such as Jackson, Andrew Young, and Louis Farrakhan went public with anti-Semitic and Anti-Israel comments. As the Antisemitism spread, the hatred didn’t infest all Black Americans but became popular with some Black leaders on the liberal side of the aisle.

Aided by the resentment of a Jewish middle class, the hatred preached by many liberal African-American community leaders like Jackson and Farrakhan spread, and mistrust began to permeate between the two communities’ leadership.

The fraying of the relationship became evident soon after Dr. King was Killed. In May 1968, a new community-controlled school board in the primarily Black Ocean Hill-Brownsville section of Brooklyn summarily dismissed 18 white teachers and administrators. In September, the school board’s action led to a series of citywide teacher strikes led by the Jewish UFT (United Federation Of Teachers) Leader Albert Shanker.

The issue in the job action was the random firing of AFT members, not faith. However, the atmosphere surrounding the strike was poisoned by African-American Antisemitism directed at the many Jewish members of the UFT. Especially the AFT president Albert Shanker. Anti-Semitic catcalls were shouted by protesters and appeared in newspapers by the Afro-American Teachers Association. A student’s anti-Semitic poem was read on the radio. The poem was called “Antisemitism: Dedicated to Albert Shanker” and began with the words, “Hey, Jewboy, with that yarmulke on your head / You pale-faced Jew boy – I wish you were dead.”

The South African anti-Apartheid movement’s leaders expanded the nascent mistrust between the two communities. They traveled throughout the United States as conquering heroes, which they were. But at the same time, they spread Jew-hatred. A leader of this hatred was Bishop Desmond Tutu. Tutu publicly complained about American Jews. He opined that Jews exhibited “an arrogance—the arrogance of power because Jews are a powerful lobby in this land and all kinds of people woo their support” (Jewish Telegraphic Agency Daily News Bulletin, November 29, 1984). In a Connecticut church in 1984, Tutu said that “the Jews thought they had a monopoly on God; Jesus was angry that they could shut out other human beings.”

The Affirmative Action movement further divided the two former allies. In the 1970s, Blacks began seeking ways to build on the civil rights act by pushing policies that supported their disadvantaged group members. Jews fought against Affirmative Action believing everything should be based on merit only, which I agree with.

Hubris caused many American Jewish leadership to believe Jews would lose the most jobs and college placement. During the now famous Supreme Court Affirmative Action case of Regents of the University of California v. Bakke in 1978. Many Black and Jewish leaders took public stances–fighting on opposite sides.

In 1979, Andrew Young, then Jimmy Carter’s ambassador to the United Nations, violated administration policy and met with a representative of the Palestine Liberation Organization. Almost immediately, Young was gone. By most accounts, he was asked to resign because he had deceived the State Department—but African-American leadership saw a Jewish conspiracy. Young’s dismissal, said Jesse Jackson, was a “capitulation” to Jews. Other Blacks castigated Jews. An article in Commentary called The Andrew Young Affair outlined the PLO incident, plus anti-Semitic comments and other acts by Young.

IN January 1984, Jesse Jackson referred to Jews as “Hymies” and New York City as “Hymietown.” He commented during a conversation with an African American Washington Post reporter, Milton Coleman. Jackson had assumed the references would not be printed because of his racial bond with Coleman. Several weeks later, Coleman permitted the slurs to be included far down in an article by another Post reporter on Jackson’s rocky relations with American Jews. Later that year, when Jackson ran for the Democratic Presidential nomination, the Jewish community, a significant voting bloc in the party, were the most fervent opponents of Jackson during the primary season.

The die was cast. The love affair between Jewish and Black Leadership, fomented by two great men, Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, was fractured by the Jew-hatred of Dr. King’s successors.

The next generation of successors sealed the mistrust.

Al Sharpton was a low-level civil rights leader looking to become “big time” by using Jews as his scapegoat. During the Twana Brawley hoax, he said that Brawley telling her story to the State’s Attorney General Robert Abrams, who was Jewish, would be “like asking someone who watched someone killed in the gas chamber to sit down with Mr. Hitler.”

On July 20, 1991, Leonard Jeffries of City College, who had a history of anti-Semitic slurs, presented a two-hour-long speech slamming those” rich Jews.” He claimed Jews financed the slave trade, controlled the film industry (together with the Italian mafia), and used that control to paint a brutal stereotype of Blacks. Jeffries also attacked Diane Ravitch (Assistant Secretary of Education), calling her a “sophisticated Texas Jew,” “a debonair racist,” and “Miss Daisy.” [as in Driving Miss Daisy].

Jeffries’ speech received enormous negative press, especially from the Jewish community leaders who wanted Jeffries fired for the bigotry. The Jewish argument worked, as Jeffries was fired as chairman of the Black studies program but allowed to stay as a professor. His position of chairman was restored after he sued the school, but the Supreme Court made the lower court reverse the decision two years later.

With each new criticism of Jeffries, leaders in the New York African-American community rushed to Jeffries’ defense. NYC’s two African American newspapers and Black radio station WLIB joined activists such as Al Sharpton, Colin Moore, C. Vernon Mason, Sonny Carson, and Lenora Fulani to showcase their approval of Jeffries’s “scholarship.” At the same time, they denounced the Jews who criticized Jeffries’ Antisemitism as race-baiters.

On August 18, 1991, speaking about the growing Jeffries controversy, Al Sharpton made his famous comment, “If the Jews want to get it on, tell them to pin their yarmulkes back and come over to my house.”

The Day after Sharpton told Jews to pin their yarmulkes back, a car in Lububcher Rebbe Schneerson’s motorcade accidentally jumped the curb and killed a young African American child Gavin Cato. The local community that had been listening to their local media who put down the Jews since the Jeffries controversy didn’t trust that it was an accident, and the Crown Heights riot began. According to the New York Times, more than 250 neighborhood residents, mostly black teenagers, went on a rampage that first night, shouting, “Jews! Jews! Jews!”

Sharpton wasn’t there on the first night when a Jewish Yeshiva student from Australia named Yankel Rosenbaum was killed. But seeing the possibility of becoming a national leader, he exploited the riot, joined on day two, and attacked the Jews.

Sharpton rode on the back of his constant scapegoating of the Jews to become a national figure. What he left behind was furthering the mistrust between Jews and Blacks.

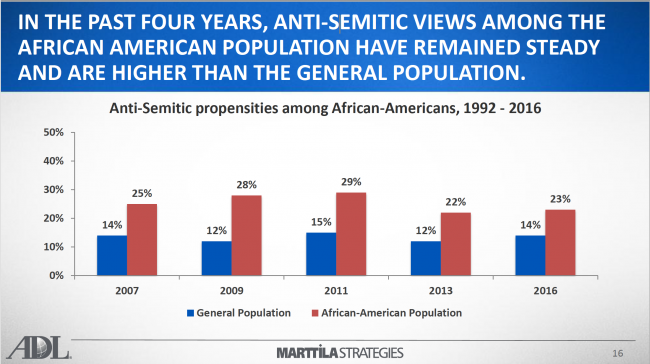

According to the liberal ADL, whose first priority is progressive politics, between 2007 and 2016, African American Antisemitism was almost twice that of the general community. While these numbers are frightening, it is essential to note that most African Americans are NOT anti-Semitic.

At the end of 2019, there was a rash of anti-Semitic incidents in the NY City metropolitan area conducted by African Americans. The worst cases were the machete attack in a Rabbi’s House during a Hanukkah Party in Monsey, NY.

Two weeks earlier, there was an Antisemitic shooting attack by two African Americans at a kosher grocery store in Jersey City. The shooting was followed by anti-Semitic comments by African-Americans in the Jersey City community, including one by a school board member.

2020 saw a string of anti-Semitic comments by famous African-Americans, including Nick Cannon, NFL wide receiver DeSean Jackson, rapper Ice Cube, author Alice Walker, former NBA player Stephen Jackson, the Black Lives Matter movement, and others Basketball great Kareem Abdul Jabbar slammed their hatred.

How do we reverse the mistrust and hatred? How do the Jewish and African American communities go back to the days of Rabbi Heschel and the Reverend Dr. King?

The answer is leadership! I am not an expert on African American leaders. Still, I suspect the issue with Black leaders is similar to that of Jewish leaders. Each community is more grass-roots than nationally led, and neither is monolithic about politics or other attitudes. But it is the national and most liberal leaders who get the press coverage, and that uni-directed media coverage also contributes to the mistrust.

If Jews demanded their leadership address the needs of their people as a priority over liberal politics and African Americans demand the same from their leadership, it would be one giant step toward bringing back the friendship of the 1960s when two men who called each other a prophet, the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, forged an alliance and friendship.

{Reposted from The Lid}

![Why You Shouldn’t Be Afraid of G-d – Soul Talk [audio]](https://www.jewishpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/light-4681014_640-218x150.jpg)

![Modesty & Matzah – Pull Up a Chair [audio]](https://www.jewishpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/matzah-1566456_640-218x150.jpg)