The deadly events unfolding in West and East Africa, as well as in Iraq, Kurdistan, Syria and as far away as Afghanistan, Indonesia and the Philippines, illustrate the macabre recovery of the Islamic State following its defeat by an international coalition in July 2017.

Like the Hydra of Greek and Roman mythology, ISIS has succeeded in regenerating itself in various parts of the world. Hundreds of ISIS fighters stormed the Al-Sina’ah (Arabic الصناعة) prison in the Ghuwayran quarter of Hasakah, Syria, on Jan. 20, 2022. The prison, run by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), held more than 3,500 ISIS prisoners (including hundreds of the terrorist group’s teen abductees, called “Cubs of the Caliphate”).

The assault liberated scores, maybe hundreds, of prisoners and held the terrain and adjacent neighborhoods for almost two weeks before a counterattack, backed by U.S. air and ground forces, forced the surrender of the remaining combatants. According to some accounts, more than 340 ISIS fighters and some 115 SDF prison guards and soldiers were killed.

Five years after the fall of Mosul, Iraq, the capital of ISIS, and the 2019 elimination of its founding leader, the self-proclaimed Caliph Abu Bakr el-Baghdadi, Islamic State had successfully healed its wounds, regrouped and sworn allegiance to an elusive new leader, the 46-year-old Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurayshi. The al-Qurayshi leadership did not last long, however. On Feb. 3 al-Qurayshi killed himself and his family rather than surrender to U.S. special forces, who had captured his hideout in an Islamist enclave in northwest Syria (reported to be under Turkish protection).

After stuttering and hesitant beginnings, ISIS has retaken the offensive, initiating and launching sophisticated assaults against targets worldwide. Islamic State uses well-trained and armed combat units that reestablished themselves under the radar of major intelligence organizations, including those of the United States, France and the United Kingdom.

Islamic State’s obituary was premature.

The new focus on Africa

Against this background, ISIS is concentrating on Africa, where 13 states have witnessed attacks against civilian targets. Attacks carried out by ISIS allies in Mali have convinced the authorities there to try and reach an arrangement with the terror group, to the detriment of the French military presence in that country.

From this point of view, Africa is the Islamic State’s success story. Observers see the group’s growing attacks (according to statistics published by ISIS, 429 attacks in 2021) as proof that the continent had become the new center of global jihad. In August 2021, the United Nations declared that “the most alarming development in recent months is [Islamic State’s] relentless spread across the African continent.”

Mozambique under attack

Since 2017, radical Islamist groups called “Al-Shabab” (no connection to the group of the same name in Somalia), affiliated with ISIS, have been widespread in the Muslim-majority Mozambican province of Cabo Delgado.

“The conflict started with an attack on the port town of Mocímboa da Praia in 2017,” the BBC reported, “and escalated as the combatants captured weapons from soldiers and gained local support.” The rebels had established contacts with Islamic State in 2019.

As reported by BBC, “In four years, the rebels have taken control of most of the five districts in Cabo Delgado province in the northeast of Mozambique.”

More than 3,000 people were killed, and more than 800,000 displaced. In March 2021, when the insurgents captured Palma, the coastal city contiguous with Total’s $20 billion development in Africa’s second-largest gas field, the French withdrew their teams from the site and suspended all activities.

Facing this development, Mozambique’s president called for foreign help. Rwanda dispatched 1,000 troops to the area, where they deployed and reached the strategic port of Mocímboa da Praia. The United States and Portugal, the former colonial ruler, provided soldiers to Mozambique to train the army to fight the insurgents. South Africa volunteered to send troops, but Mozambique preferred Rwanda. South Africa decided to send ships and planes to Pemba, and 1,500 South African soldiers drove in armored convoys into Mozambique. Botswana sent armored vehicles with 300 soldiers.

As of February 2022, the situation has stabilized, but foreign troops are still present to protect the main cities of Cabo Delgado from ISIS attacks, leaving the jungle and the periphery to the exclusive control of ISIS-Mozambique.

Nigeria: Will the ‘Islamic State in the West African Province’ (ISWAP) replace Boko Haram?

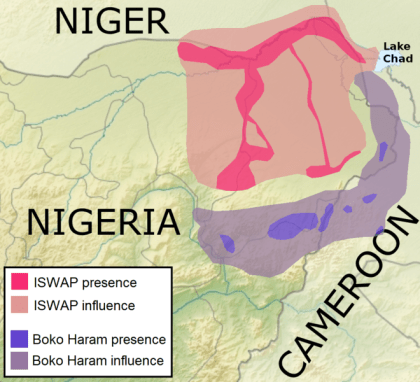

In Nigeria, the army was unable to quash the Boko Haram terrorist organization. Ostensibly, Islamic State, better known as the ISWAP (Islamic State in the West African Province), could. In a dramatic development, in 2021, Boko Haram, the radical Islamist terrorist organization present in Nigeria and the Chad Basin, reached a crossroads, as thousands of its combatants abandoned their units and surrendered to ISIS, following the defeat of their organization and the death of their leader, Abu Bakr Shekau. As a result, ISWAP inherited the territories of Boko Haram in the Sambisa Forest, which was the haven of Boko Haram and the location from which the terrorists exerted their grip over northeast Nigeria and Lake Chad in the east including north Cameroon and Niger.

The conflict is estimated to have contributed to the deaths of about 350,000 people, with up to three million more displaced. According to Stig Jarle Hansen, a specialist on jihadist and Islamic groups in Africa, there have been reports that ISWAP is attempting to set up a rival government, funding development projects and levying taxes to win popular support. ISWAP will probably continue Boko Haram’s strategy and try to enlist similar organizations in the Sahara belt while exploring areas in the center and south of the continent.

According to ISIS’s annual report, the group recorded operations in Egypt, Tunisia, Mali, Niger, Congo (probably the DRC), Somalia, Libya, Chad, Uganda and Burkina Faso. ISIS will probably concentrate on Mali and Burkina Faso in the coming months, two countries that are key to controlling the Sahel belt. The United Nations is also alarmed by the resurgence of ISIS in southern Libya, an area that allows the penetration of the porous borders of Libya’s neighbors to the south, east and west.

Problems and prospects of the ISIS penetration of Africa

Despite the success of ISIS in consolidating its positions in Africa, it still faces problems. ISIS is now immersed in conflicts with the nomadic Fulani clans and farmers, urban and rural dwellers, and in responding to the intensifying military threat posed by the coalition of states (European, American and African) dedicated to eradicating it. Moreover, the recent elimination of three jihadist leaders—Abu Bakr Shekau, Abu Musab al-Barnawi and Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahrawi—emphasizes the fact that internal disputes, tribalism and factionalism are serious hurdles facing Islamic State expansion in Africa.

The Islamic State West African Province has so far proven its inability to create and structure a more unified jihadist movement in Africa. “The Islamic State’s West African Province is no longer on the rise,” reported Stig Jarle Hansen in November 2021. “It has been checked by its own factionalism and its involvement in local conflicts. But the Islamic State will almost certainly rebuild.”

Even the defeated Boko Haram managed to survive, fight back and reestablish itself in the confines of Lake Chad, away from the Sambisa Forest.

The Islamic State reported that in 2021 it conducted 2,748 operations that resulted in the death and injury of 8,039 individuals. Almost 50 percent of the operations were conducted in Iraq and Syria (1,127 and 368, respectively), causing the death and injury of more than 2,800 individuals. ISIS, whose base is in the Idlib enclave in Syria and protected by Turkish dominance, has pursued efforts to enlist new recruits from Europe and the Arab world. Its most recent success is the recruiting of scores of Lebanese from the Tripoli area who, because of the economic plight in Lebanon, see joining ISIS in Iraq as a way to support their families back in Lebanon.

The report indicates activities in Indonesia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India and the Philippines but omits activities in Europe, Morocco, Algeria, Central Africa. The report does not provide an explanation about these activities; there is no doubt that their omission is not accidental.

Conclusion

The 2017 defeat of Islamic State has proven not to have been final. It has managed to reorganize and, after a few stutters, has been recognized as having recovered from its losses. There is little doubt that the elimination of Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurashi by U.S. special forces created a temporary vacuum in leadership, and that it could take time to re-organize under new leadership. Yet ISIS will survive, given the continued polarization between Shi’ites and Sunnis, and since the political and socio-economic reasons that were sources of its creation are still present. Five years after succumbing to the international military coalition, ISIS has managed to conquer new territories, mainly in Africa, even though it is confronted with unexpected difficulties due to most African states’ particularism and sectarian politics.

It is important to stress that half of all ISIS operations in 2021 were carried out in Iraq and Syria, which remain the basis for ISIS strategy, despite efforts invested in eradicating its presence. The political reality of both Syria and Iraq can only suggest that ISIS will continue to develop once it has chosen a successor to al-Qurashi.

Col. (ret.) Dr. Jacques Neriah, a special analyst for the Middle East at the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, was formerly a foreign-policy adviser to Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and the deputy head for assessment of Israeli Military Intelligence.

![Sacred Rage! – Pull Up a Chair [audio]](https://www.jewishpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/baby-623417_640-218x150.jpg)

![Victory In Gaza – The Jay Shapiro Show [audio]](https://www.jewishpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/injury-6860646_640-218x150.jpg)