Last week, while reading online articles about the political situation in and surrounding Israel, I wasn’t really expecting to come across articles discussing Chumash.

Then again, with a title like Abraham The Zionist, and this week being Parshas Chayyei Sarah, Rabbi Chaim Steinmetz’s article in JNS should not have been a surprise.

The Parsha begins, of course, with Avraham buying a burial plot for his wife Sarah in Hebron, and the Torah goes over the negotiations for the land in some detail. The commentators ask why so much attention is paid to the circumstances surrounding the sale and they offer various answers.

Rabbi Steinmetz refers to one commentator in particular:

As Ibn Ezra [23:19] notes, the purchase of a burial plot for her marks the beginning of the future Jewish state. [emphasis added]

In an article on the HaTanakh.com website, Rabbi David Silverberg makes a similar point and expands on it. He notes that

Ibn Ezra further comments that this incident is significant in that it marks the first stage in the fulfillment of God’s promise that Avraham and his offspring would possess Eretz Yisrael.

This promise is made to Avraham earlier in Bereshit 17:8:

To you and your offspring I will give the land where you are now living as a foreigner. The whole land of Canaan shall be [your] eternal heritage, and I will be a G_d to [your descendants]. [translation: Aryeh Kaplan]

But Avraham is not the only one of the Avot (forefathers) who bought land in Eretz Yisrael. Just as Avraham bought land in Hebron, so too did Yaakov buy land — just outside of Shechem [33:19].

In fact, Avraham and Yaakov were not the only two who bought land in Canaan — just as Hebron and Shechem were not the only two areas where land was acquired on behalf of the Jewish people.

In her New Studies in Bereshit (p. 208), Nechama Leibowitz quotes from the Midrash in Bereshit 79:7

This is reminiscent of the first Rashi in Chumash, which explains that the Torah begins with the creation of the world in order to provide Jews with a counter-argument against those who would accuse them of “stealing” the Land of Israel.

Hebron.

Shechem.

Jerusalem.

All 3 cities established as Jewish cities, central to Jews.

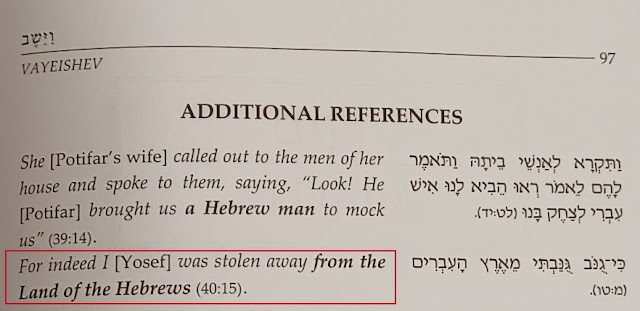

In his Sefer, Eretz Yisrael in the Parashah: The Centrality of the Land of Israel in the Torah, Rabbi Moshe D. Lichtman points out another verse in the Chumash that highlights this Jewish connection to the land:

Land of the Hebrews?

However we understand this phrase, this verse indicates that on some level, despite being a small group — albeit 70 members — living in Canaan, the family of Yaakov was recognized for its connection to a specific area in that part of the land of Canaan.

This points to the ancient history and connection of the Jewish people in the land that long precedes the appearance of the Arabs, who after all are indigenous to Arabia.

But there are Jewish groups today who recognize the Jewish connection to Eretz Yisrael, yet still maintain their distance while at the same time demanding the right to have a say in how the Jewish state conducts itself.

I mention this because of another article I came across this past week with an unexpected interpretation of the Chumash. While I enjoy Melanie Phillips’s articles, I generally don’t read her for her insights on the Torah. But she did have an interesting perspective on Jewish groups who criticized the recent Israel elections and took it upon themselves to advise Netanyahu on who should not be included in his cabinet.

In Dragons and Dragon-Slayers in Israel and America, Phillips writes:

Israel is indeed a state for the Jewish nation. However, membership in a nation confers obligations on its people to behave as a nation.

After all, the Torah itself tells us that when the tribes of Reuben, Gad and half of Manasseh said they wanted to settle east of the Jordan because the pastures there were more fertile, they were told they could do so only on condition that they first fought alongside the other tribes to conquer the land of Israel.

But American Jews such as those in Mercaz Olami [the Zionist umbrella arm of Conservative-Masorti Judaism] don’t feel bound by any such obligation. They not only choose not to live in Israel but also choose not to fight in its defense.

Instead, ensconced in a faraway land they prefer, they lob verbal missiles at the tribe from which they have separated themselves when it defends its Jewish identity in ways of which American Jews disapprove.

Today, the long and established Jewish connection to the land does not automatically guarantee an equally well-established sense of Jewish identity and pride in the Jewish people.

![Tears of Joy Today, Danger & Bloodshed Tomorrow – The Tamar Yonah Show [audio]](https://www.jewishpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/temple-7575573_640-218x150.jpg)

![How To Stop Being Jealous and Start Living – Soul Talk [audio]](https://www.jewishpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/jealous-8493844_640-218x150.jpg)