Military and Nuclear collaboration with South Africa was a very sensitive issue that was raised in Section III of the report of the Special Committee Against Apartheid, [1] [11] (Blum, op.cit. 218-219).

Significantly, the Special Committee Against Apartheid did acknowledge that in November 1977, Henry Kissinger, then US Secretary of State, had “asked the

Israeli Government in early 1975 to send troops to Angola in order to co-operate with the South African army in fighting the Popular Movement,” according to the British weekly newspaper The Economist of November 5, 1977. The paper added that Israel was asked “to provide South Africa with naval, armoured electronic and counter-insurgency equipment. Israel promised to supply South Africa with six Rechef-class fast war ships fitted with a highly advanced model of the Gabriel surface-to-surface missile, automatic 76-mm guns, anti-submarine torpedoes, a submarine detection system and electronic equipment. The report continued that three of the boats had already been delivered.”

“The South African crew had their training at naval bases in Israel. Three other boats were expected to be delivered by mid-1978. South Africa was to invest in the Israeli military industry in return, South Africa was scheduled to get the first four or five boats, which are the new versions of Rechef, to be produced in 1979-1980. The new boat Rechef is larger than the current one, it is able to carry a helicopter and is armed with submarine detection devices and anti-submarine missiles. It also will be equipped with Gabriel surface-to-surface missiles. Forty South African engineers and technicians went to Israel to watch over the work at the Haifa shipyard.” [2]

Foreign press reports claimed Israel used its “highly developed technology to equip helicopter squadrons in South Africa with night‐visibility equipment.” When asked if there were Israeli military personnel in South Africa, Israeli officials acknowledged there were 5,000 Israelis who had emigrated to South Africa, and this probably included some trained individuals with technological knowledge of Israeli products. [3] (William E. Farrell, “Israeli Tours South Africa As Arms‐Trade Furor Grows,” The New York Times (February 10, 1978).

The Ghanaian Times (Accra) reported that Israel is supplying South Africa with “Kfir” fighter bombers, missile boat personnel and armoured carriers, and sophisticated electronic equipment.” The Sunday Chronicle (Lagos, Nigeria) reported that a military communications factory “had been commissioned outside Pretoria.” [4] (“Special Reports of the Special Committee Against Apartheid,” op.cit.10.)

South Africa’s modern armed forces had sophisticated aircraft, artillery, destroyers and submarines. Patrol boats allegedly sold by Israel to South Africa were “minuscule” compared to these weapons supplied by major Western powers. Yet, the UN marked Israel alone for condemnation. Jordan’s sale of British-made fighter planes and missiles in 1974 seemed to have been overlooked. Also ignored was Israel’s announcement in the fall of 1977 that the country would comply with the recently declared Security Council’s mandatory arms embargo. [5]

Nuclear Technology

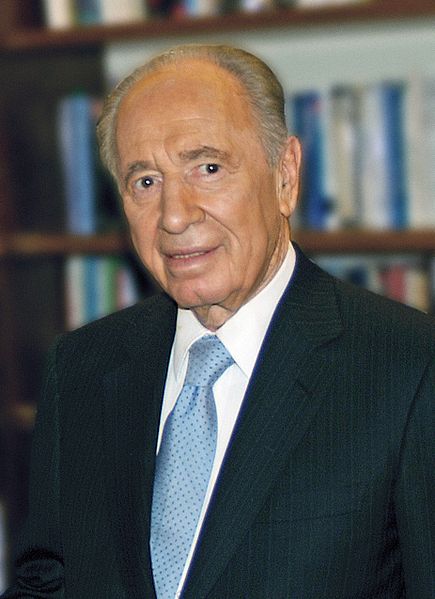

Shimon Peres, “who served as the de facto head of the Israeli nuclear program during its early years,”[6] explained the rationale for acquiring nuclear technology. “At the time, the Arab world had made commitments to Israel’s annihilation a litmus test for leadership; indeed, every Middle Eastern politician or general who hoped to ascend had to prove he was more intent on destroying us than his rival was. I believed that sowing doubt in their ability to actually do so was our highest security imperative.” For this reason, he asserted, “The reputation of nuclear is deterrence. And deterrence, I believed, was the first step on the path toward peace…. This was the security of knowing the state would never be destroyed.” [7]

Development of South Africa’s nuclear program began in 1949 with the purchase of hardware and expertise from the US, Britain, France and Germany. In 1976, the West severed the connection after determining that under the pretext of developing nuclear energy for peaceful use, they were creating nuclear power for military purposes. [8]

Peres initially approached France since “as the country with whom we’d built our closest friendship, France represented an opportunity.” Furthermore, “As Europe’s most advanced country in the nuclear field, it also represented our best option. Indeed, the French industry had built teams of engineers and scientists with precise expertise. France’s universities were the best place in the world to study nuclear physics. They had at their disposal everything we would need to build a nuclear reactor.” [9]

Sasha Polakow-Suransky, a former editor of Foreign Affairs, exposed the extent of this relationship forged in the mid-1970s by Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and defense minister Shimon Peres in his book The Unspoken Alliance: Israel’s Secret Relationship with Apartheid South Africa. [10]

Alliance Intensified

Israel’s alliance with South Africa intensified after the October 1973 Yom Kippur War as their mutual military and economic interests fueled the relationship for the next three years. During the war, when Israel desperately needed spare parts for her damaged French Mirage jet fighter planes, South Africa provided the parts. [11] The failure of the US to respond immediately to Israel’s dire plea for military hardware during the critical opening days of the conflict, when she suffered significant setbacks on the battlefield, drove Israelis to radically increase her domestic arms industry. [12]

After the war, most African nations abandoned Israel in exchange for Arab petrodollars and threats of Arab economic pressure. The seemingly endless rise in oil prices had taken a severe toll on much of Africa’s economy. [13] Though the US supported Israel and South Africa to various degrees, neither country had a joint defense agreement to feel secure enough to depend on the US for their continued existence. The absence of America’s unconditional military support led Israel to a feeling of vulnerability.

With the generated surplus from their weapons industry, Shimon Peres sought access to South Africa’s export market and their funding to develop new weapons. In the process, the exports helped rectify Israel’s severe trade imbalance and provide work for scientists, engineers, and technicians returning with expertise from abroad. As Angola and Mozambique came under Soviet patronage, the leaders of South Africa turned to Israel in desperation for weapons—the only country willing to help them. [14]

According to one report, South Africa was Israel’s second- or third-largest trading partner because of arms sales, and both collaborated considerably on nuclear technology. No less than 20 percent of Israeli export income emanated from South Africa in 1985. [15]

This collaboration lasted throughout the most turbulent period of the apartheid regime—a relationship essential for Israeli security and financial well-being. Because of this association Israel has been chastised. Sometimes it is easy to forget that Israel had to contend with the Arab League’s boycott, attempts at the UN to undermine her legitimacy, and diplomatic isolation, and encircled by UN member states actively seeking her demise. [16]

Golda’s Response

In 1958, when the Israeli Minister of Foreign Affairs Golda Meir visited Africa for the first time, she intended to speak to a group of black leaders in Accra, Ghana about public health, infrastructure and agriculture. Instead, she found herself at a table surrounded by 60 “skeptical” men who backed the fight in the Arab countries of North Africa against French colonialism and were quite disturbed by Israel’s relations with France. The Algerian representative stood up to insist Israel justify the country’s involvement with a government engaged in a “ruthless and brutal war against my people,” and is the primary enemy denying self-determination to the people of Africa. [17]

Golda did not equivocate: “Our neighbors…are out to destroy us with arms that they receive free of charge from the Soviet Union…. The one and only country in the world that is ready…to sell us some of the arms we need to protect ourselves is France.” She then turned to the audience and asked: “If you were in that position, what would you do?” They did understand. [18]

When the African National Congress publicly announced that Palestinian Liberation Organization leader Yasser Arafat, Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi, and Cuban dictator Fidel Castro were among their furthermost allies, American leaders viewed this in perspective. [19] After all, the U.S. collaborated with the Soviet Union’s dictator Joseph Stalin during World War II to defeat the Nazis.

A Final Note

Robert D. Kaplan an American author, reminds us that analyzing “real history, is not the trumpeting of ugly facts untempered by historical and philosophical context. Realism is about the ultimate moral ambition in foreign policy: the avoidance of war through a favorable balance of power.” [20]

From the very beginning of Israel’s birth, the country has been faced existential threats. Those not involved in defending the Jewish people have the luxury to pontificate how they should act, yet as Kaplan observes, “Ensuring a nation’s survival sometimes leaves tragically little room for private morality. Discovering the inapplicability of Judeo-Christian morality in certain circumstances involving affairs of state can be searing. The rare individuals who have recognized the necessity of violating such morality, acted accordingly, and taken responsibility for their actions are among the most necessary leaders for their countries, even as they have caused great unease among generations of well-meaning intellectuals who, free of the burden of real-world bureaucratic responsibility, make choices in the abstract and treat morality as an inflexible absolute.”

Footnotes

[1] Yehuda Z. Blum, For Zion’s Sake (Cranbury, New Jersey: Cornwall Books, 1987), 218-219.

[2] Special Reports of the Special Committee Against Apartheid General Assembly Official Records : Thirty Third Session Supplement No. 22A .(A/33/22/Add.lland 2):7.

[3] William E. Farrell, “Israeli Tours South Africa As Arms‐Trade Furor Grows,” The New York Times (February 10, 1978).

[4] “Special Reports of the Special Committee Against Apartheid,” op.cit.10.

[5] Chaim Herzog, Who Stands Accused? Israel Answers Its Critics (New York: Random House, 1978), 154; “Special Reports of the Special Committee Against Apartheid,” op.cit.10. for a review of Africa’s special and unique place in Israel’s foreign relations see Dr. Arye Oded, “Fifty years of MASHAV activity” Jewish Political Studies Review, Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs 21:3-4 (Fall 2009) (October 26, 2009); Ehud Avriel, “Israel’s Beginnings in Africa, 1956-1973, Memoir,” in Israel in the Third World, Michael Curtis and Susan Aurelia Gitelson, Eds (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Books,1976), 69-74.

[6] https://ahf.nuclearmuseum.org/ahf/profile/shimon-peres/

|

Shimon Peres (1923-2016) was an Israeli politician who served as the de facto head of the Israeli nuclear program during its early years.Peres was born in Vishneva, at the time part of Poland. In 1934, his family moved to Tel Aviv in then-Palestine. As a young man, Peres helped organize…

ahf.nuclearmuseum.org

|

.

[7] Shimon Peres, “How Israel Went Nuclear,” Tablet (September 11, 2017).

[8] Yossi Melman, “Did Israel play a role in 1979 south Africa nuclear test?” Haaretz (August 2, 2009).

[9] Peres, op.cit.

[10] Sasha Polakow-Suransky, The Unspoken Alliance: Israel’s Secret Relationship with Apartheid South Africa (New York: Vintage Books, 2011), 7; Sasha Polakow-Suransky, “Time to come clean: It’s time for Shimon Peres to tell the truth about Israel’s military cooperation with Apartheid South Africa” Haaretz (June 4, 2010); Chris McGreal, “Revealed: how Israel offered to sell South Africa nuclear weapons,” The Guardian (May 23, 2010); Chris McGreal “Israel and apartheid: a marriage of convenience and military might, The Guardian (May 23, 2010); Avner Cohen, Israel and the Bomb (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998); David K. Willis, “How South Africa and Israel are maneuvering for the bomb,” The Christian Science Monitor (December 3, 1981);. Avner Cohen, “Israel’s Nuclear Secrets That Peres Shared With Kissinger in 1965,” Haaretz (December 14, 2020).

[11] Polakow-Suransky, The Unspoken Alliance, op.cit.6, 72.

[12] Ibid.76.

[13] Herzog, op.cit. 155.

[14] Ibid. 77-84.

[15] James Kirchick, “The Unspoken Alliance, by Sasha Polakow-Suransky,” Commentary (September 2010; Polakow-Suransky, op.cit. 49, 72, 83, 141, 149.

[16] James Kirchick, op.cit; Alex Grobman, “History of the Arab Boycott and Its Resurgence,” The Jewish Press (July 24, 2021).

[17] Polakow-Suransky, The Unspoken Alliance op.cit. 27.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid. 196.

[20] Robert D. Kaplan, “In Defense of Henry Kissinger,” The Atlantic (May 2013).

[21] Ibid.

Dr. Alex Grobman is the senior resident scholar at the John C. Danforth Society, a member of the Council of Scholars for Peace in the Middle East and on the advisory board of the National Christian Leadership Conference of Israel (NCLCI). He has an MA and PhD in contemporary Jewish history from The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.